In an eighteen-part series which regularly splits the soul of its protagonist, can we say the Dale Cooper who returns “one hundred per cent” in Part 16 is the original Cooper?

Answers to this question are likely to differ from viewer to viewer. My answer, like Cooper in the 1991 series finale, is split in two. In one direction, I acknowledge the real-world production of this art and the intents of those who produced it. In the other, I fall back on my understanding of Twin Peaks as a ‘world’, the type of storytelling we’ve been engaging with all this time, the fact it makes new statements of itself regularly and that here in its finale it’s taught us to read a whole new physics, in terms of the metaphysical ‘rules’ of the world of Twin Peaks, and in turn to read a whole new philosophy about what this story means.

In the real-life production of Part 16, I recognise the possibility, probability perhaps, that Lynch and Frost never indicated to Maclachlan or anyone else that this wasn’t Coop as we knew him. I don’t think ‘this is not quite the same man’ was baked into the performance by Maclachlan, nor visual storytelling by Lynch, in Part 16. From that perspective, if Maclachlan plays him as the original Coop, then what we see here is the original Coop.

I do, however, believe there was at least a brief that there is something wrong with Coop in Parts 17 and 18, and that these scenes featuring him don’t all represent the same character. Maclachlan plays them distinctly; the character is written differently. I would argue Maclachlan plays a new version of the same character most times he appears in a new scene in Part 18.

Within the content of the show itself, the final few episodes and the finale especially present an entirely new mode of Twin Peaks. It’s completely in conversation with its predecessors, but is telling a new version of this story, literally rewriting its history, and forming a whole new set of stories based on the old one. Cooper steps through time to the night Laura Palmer is killed, takes her hand, and leads her through the woods to safety. Except he doesn’t. He can’t. Laura, we discover, must always die in these woods. As always, Cooper is beholden to the rules of the abstract world of the Lodge. Like Orpheus, Coop turns to look at Laura, his Eurydice, who has vanished. Woodland silence, wind in the trees. Broken by a formless, nebulous scream: that of Laura Palmer, fated to a brutal death in the woods at the hands of Bob or Leland or otherwise on 24 February 1989.

In the final episode, now that Coop has broken time and unwritten the fundamental throughline of the show, the story breaks away from The Return, arguably all of Twin Peaks, almost completely. Coop, in his chauvinistic, white-knight grandeur, robbed the people of Twin Peaks of twenty-five years of life. Pete Martell went fishing that morning, uninterrupted by a corpse washed ashore. In 2017, Sarah Palmer wails in agony. Dispossessed of her grief, her despair. In a fit of rage against the dying of the light, she stabs her framed photograph of her dead daughter, whose existence dictated her life, from her adolescence in 1950s New Mexico to now. If her daughter doesn’t die at the hands of her husband, what is she, twenty-five years later? Nothing.

Non-existent.

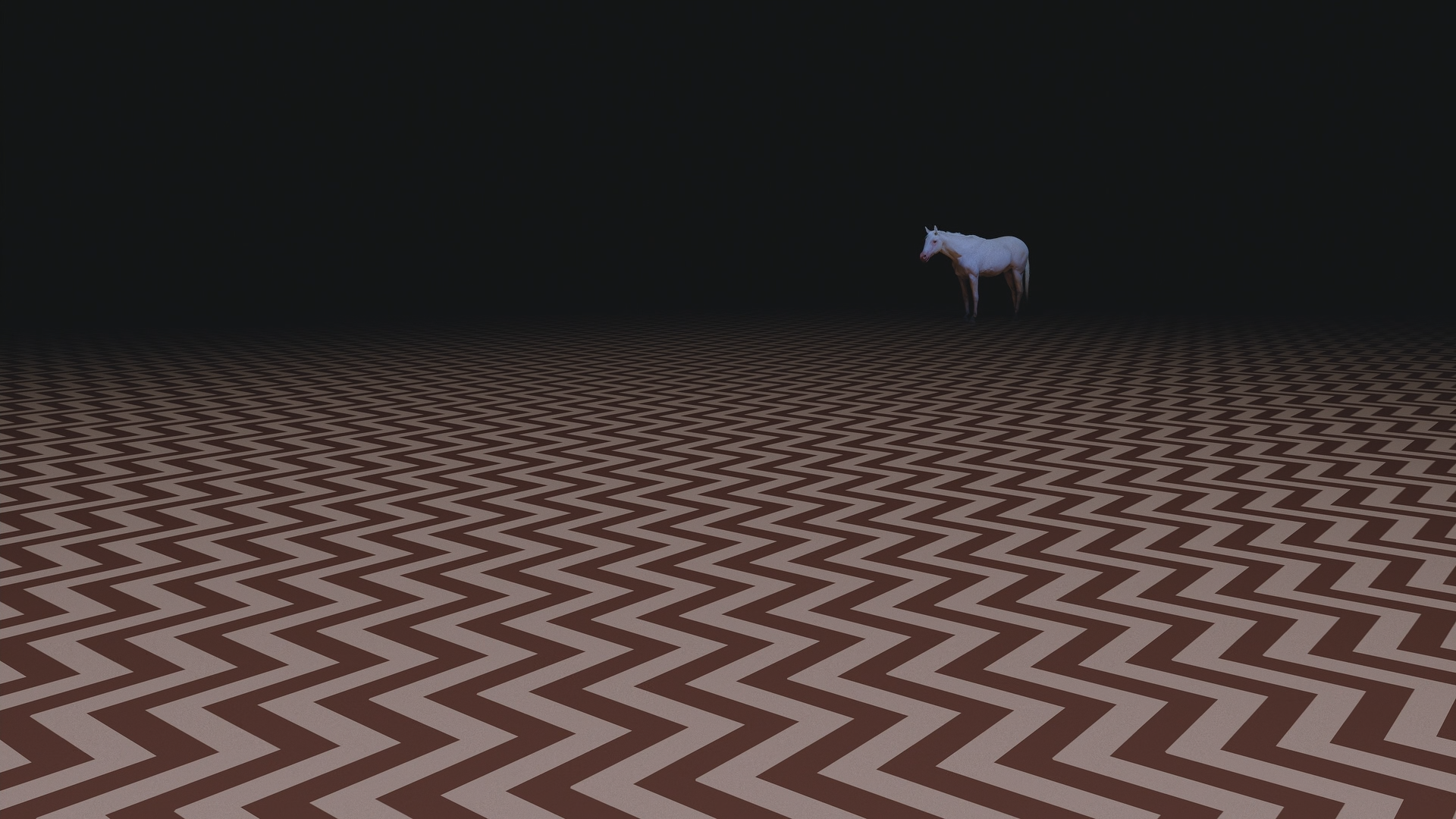

There are many universes, many timelines. Frost and Lynch never provide us with adequate terminology to describe the concepts they create visually, so the comic book vocabulary which has come to pervade science fiction and fantasy will have to do. We are shown a Matrix-like world of an uncountable number of machines in the shape of Phillip Jeffries existing in the place we were introduced to in Part 3, a dimension in a purple hue with industrial buildings atop an endless ocean, a sort of bridge dimension between our world and the Lodge space. If the Waiting Room and its equivalents – the Convenience Store, the Roadhouse, the Fireman’s roaring-twenties cinematic manor – may be called liminal, then the purple place is purgatorial. The implication seems to be that whole universes with variations on people, characters, exist inside these machines. Now, not only are there an uncountable number of universes, there exists also an infinite number of shards of timelines, shattered by Dale Cooper’s hubris.

In one timeline, the first of several presented to us in the finale, a Diane and a Coop hop ‘universes’, abandoning ship, and they seem to know much more about what’s going on than we do. Not only does Coop know more than us, he also knows more than he seemed to in Part 17, and certainly 16. On the other side, Diane sees a copy of herself from afar; Dale and Diane have eerie, unreciprocated sex in a sort of reversal of the last incident of sexual nature between Cooper and Diane in which the Bad Dale assaulted her; Diane, now Linda, leaves Cooper, Richard, and he will never see her again. Richard, Cooper progresses on his mission to find Laura Palmer, Carrie Page; and the Tremonds live at the Palmer house.

Before he tried to save Laura Palmer by escorting her from the woods in which she was fated to die, Coop spoke with the Evolution of the Arm, who asked if he was here about “the story of the little girl who lived down the lane.” This is how Lynch asks us to communicate about Twin Peaks, about the stories of Twin Peaks, its fundamental story and all others. There are hundreds of splintered pieces of story in Twin Peaks. It brims with soap opera and stories about individuals, stories that lead nowhere, stories you only hear one side of, stories you hear in pieces over twenty-five years.

The story of the neglected Horne daughter. The story of the only East Asian in Washington State. The story of the insurance-broker from Las Vegas. The story of the Texan who went with the FBI agent to get out of Dodge.

Twin Peaks ends on a series of finales for different stories about Coopers, Dianes, Lauras. There is story upon story in this world, happening at the whim of unnamed, obscure cosmic forces, and the Coopers’ innate motivation to save Laura Palmer.

No, the man we see in Part 16 is not the original, bona fide Special Agent Dale Cooper, because he can’t be. Not only narratively because of all the time he spent in unfathomable realms, falling through space, but also because it’s the intention of The Return for its viewer to consider change and renewal throughout.

In the sense that Sarah Palmer is inhabited by the Lodge, so is Cooper, but what we’re being shown in the finale is beyond just Cooper as overcome by spiritual interdimensional forces. It’s Cooper’s soul as split, by the creation of different versions using the ‘seed’ of him, and by his own disruption of time in “going in,” as kettle-Phillip Jeffries puts it, to save Laura.

I used to think of the second Cooper in Fire Walk With Me, and Jeffries’ line “who do you think this is there?”, as indication that when this happened — and it’s intentionally unclear in Fire Walk With Me where in events this appearance of Jeffries took place, hence Gordon and Albert referring to it as a dream in The Return — Cooper was already split. The Return goes to great lengths to confirm that is true, but not because the Cooper there was the Bad Dale that we’ve followed throughout The Return, or some incarnation of Bob, or any other narrative-bound possibility; instead, because there are so many Coopers, and we’re being told, loudly, that there always has been.

Leave a comment