Shakespeare’s final solo play, The Tempest (1611), features a protagonist who, of his own volition, gives up the magical powers he cultivated from the land he claimed as his own, frees the indigenous creatures he enslaved and utilised in his mission, and appears to prepare to leave the island to return to Milan. There are plenty of other metaphorical links between Shakespeare and Prospero, but at its core, this character seems to be Shakespeare projecting his retirement onto his writing. He’s giving up playwrighting (as a solo professional), ‘freeing’ the actors he had employed in his company the King’s Men from his work, and leaving London to return to Stratford-upon-Avon.

Of all thirty-seven solo plays he’s known to have written, only ten include epilogues. The Tempest includes an epilogue in which Prospero admits that, without the remarkable magical “charms” he acquired through the study of books in a land which was foreign to him, he has not much “strength” of his own:

Now my charms are all o’erthrown,

And what strength I have’s mine own,

Which is most faint.

Prospero asks the audience that, since he has his “dukedom got,” let him not “dwell in this bare island” but release him from his “bands / With the help of your good hands.” Prospero’s restored title grants him the ability to return home to Milan and be freed of the island on which he had been imprisoned, conducting his work. To be released from his metaphorical shackles, he requires the spectators in the Globe to put together their hands. With the final mark of appreciation at the end of his last show, Shakespeare requires, as ever, the approval of his audience: he requires that they clap. On doing so, they release him. “Let your indulgences set me free”: the final line of Shakespeare’s final play.

Like Shakespeare’s Tempest, the works of David Lynch seem, through characters’ actions and dialogue or the setting in which they participate or both, to be conscious of their performative nature. As a writer-director he appears interested in the concept of performance-within-performance, a metanarrative indication that the film is aware of its own performance, its fiction.

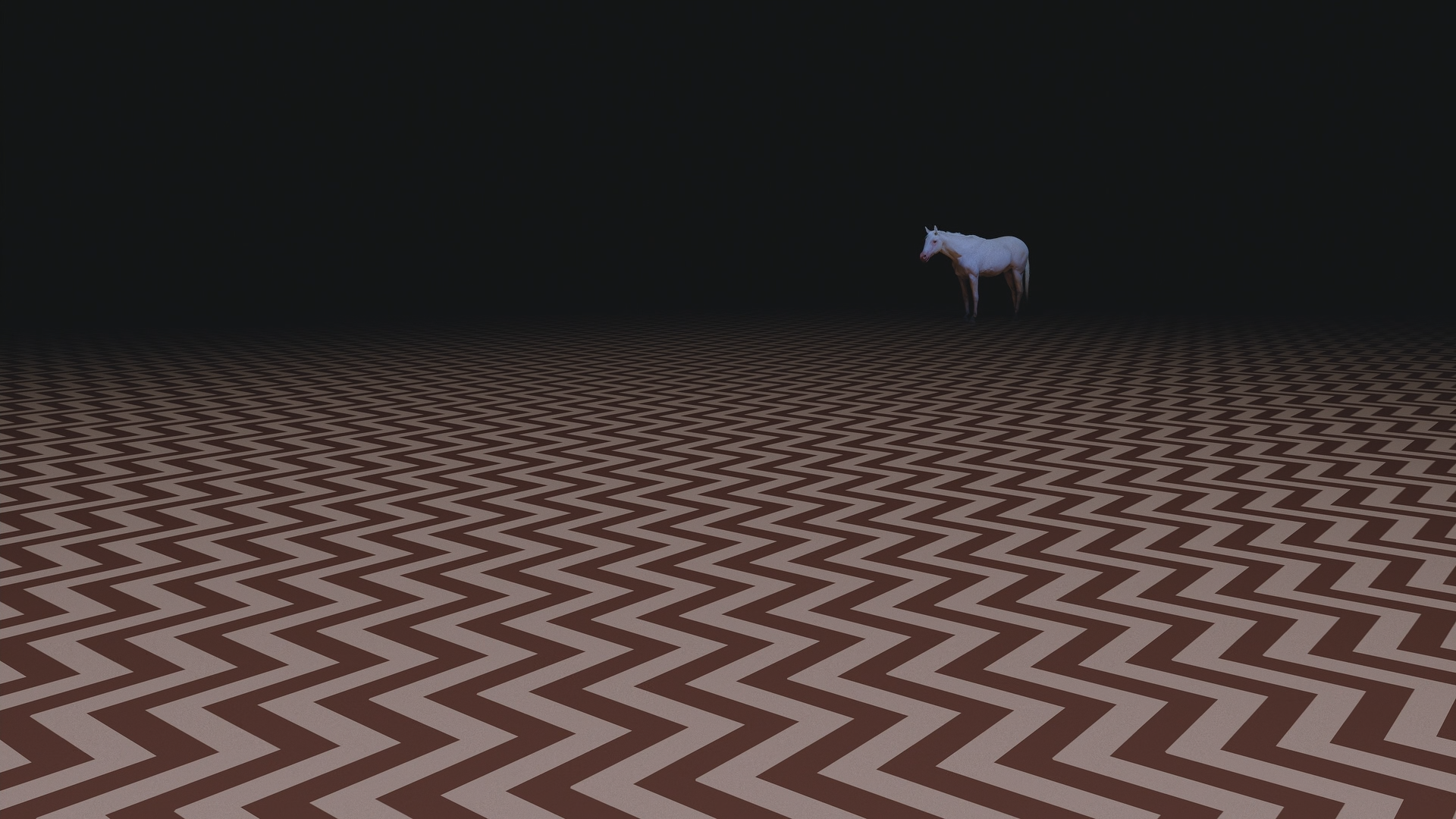

Performance and spectatorship are principal to Lynch. In Twin Peaks, the Black Lodge is shrouded by tall red drapes identical to stage curtains. The only respite for Eraserhead’s protagonist is observing or being on stage with the Lady in the Radiator. Frank Booth’s victim in Blue Velvet is a professional singer at a nightclub; it’s her fame and stage presence which leads to her trouble with Frank in the first place. Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire, to different ends, are commentaries on the Hollywood filmmaking industry, and heavily feature scenes of sets and performance. Laura Palmer’s perfect schoolgirl life is performative. She performs to convince her family and friends she does not take drugs; she does not lead a second life in which she has fetishistic orgies with grown adults and know of a ring of groomed and trafficked teenage girls in and around Eastern Washington.

When Cooper enters the Lodge, there’s a sense that he is going backstage. In the universe of Twin Peaks, the town is like a surrealer, absurder anomaly that exists in an already surreal, absurd world. Cooper comes from a strange world and, on entering the town of Twin Peaks, finds himself in a stranger one.

Cooper and Gordon Cole’s department of the FBI are spectators to the town, which takes, or rather becomes, in this analogy, a stage in its right. After learning the ropes of the onstage absurdism in Twin Peaks – in which the local response to a murdered girl is deranged melodramatic sobbing over the Tannoy by her high school principal, cryptic clues left by an eccentric psychiatrist donning Hawaiian shirts and anaglyph glasses, a bizarre sense of shared responsibility among the townsfolk and the general agreement that there is something in these woods – we are allowed backstage, to see the inner workings of the town, what makes it quite so peculiar, what gives it its supernatural edge. We learn that what exists backstage are spiritual forces beyond human comprehension.

The small man in the Lodge identifies himself as The Arm and performs a little dance for Cooper. He tells us “I sound like this” and makes a silly noise with his mouth. Cooper is confronted with a gender-ambiguous performer singing about sycamore trees. It is unclear both to Cooper and to us what exactly the Lodge spirits want or do, what the laws of physics of the dimension they exist in are, and why they behave…like that. What is clear, though, is that they love to perform.

The world of Twin Peaks is upside-down, a mirror of reality. In it, Lynch and Frost have created an inverse world typical of the early modern era of English theatre. Shakespeare and his contemporaries created satirical worlds in their comedies in which their contemporary Elizabethan/Jacobean value system is reversed or altered. Social order is deconstructed by the early modern satirist and reorganised, offering spectators a mirror reality. In a Mark Fisher-esque, capitalist realist way, this type of spectatorship is purgative. It gives spectators a chance to revel in activities considered immoral and live vicariously through characters who might, for example, fool other characters that they are the opposite sex by dressing as such, or flirt with characters of the same sex, or decry God and Christianity, or party too hard and sin too much. It’s a Bacchanalian tradition, evocative of the Roman festival Saturnalia in which, for a single day, slaves pretended to be masters and masters slaves. It’s a catharsis and, almost paradoxically, reinforces ‘the rules’. In abandoning the rules on stage or in carnival, revellers can return to the real world cleansed of their antisocial desires, like Fisher suggests returning to the real world after observing a performance of revolution satisfies the urge to revolt. Bakhtin calls the literary equivalent of this, your Shakespeares and your Lynches, the carnival mode.

Bakhtin’s carnival symbolises the dismantling of structure and control. Normative order is replaced by strange and arguably immoral phenomena, contrary to the moral foundations of real contemporary society. Performance in Lynch’s work is symbolic of the abandonment of social order. Laura Palmer’s homecoming queen performance is offset by her other performance, the drug-abusing femme fatale type – in reality, she is neither.

Laura rejects order. She rejects the moral value system imposed on her. For Laura, so long as she is in control, even (or especially) if the act she is in control of is self-destructive, she is comfortable. Performance is her strength. Manipulation of both sides is her strength. She can manipulate her mother and her teachers and the pretty boys at school, and she can manipulate Jacques and Leo and the statutory rapists and child sex traffickers and paedophile truck drivers, and she can exercise some form of control over Bob.

Performance in the Black Lodge is the visual representation that this spiritual world exists outside of the rules of reality, it is through the looking glass, forget what you thought you knew.

The Arm, similarly to Laura, enjoys the psychological manipulation and confusion performance causes his spectator. Performance in the hellish Hollywood of Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire is run by an apparently criminal cult, inspires sexual perversions, obsessive and intrusive desires and thoughts, and destroys its victims’ sense of reality and real life entirely; Hollywood, like the Black Lodge, is a dimension unto itself with its own laws of physics and rules of order. Characters seem to be conscious they are characters.

Some Lynch characters build characters for themselves. Lost Highway, Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire each feature protagonists who create false realities, alternative versions of themselves, and are to some degree aware – as we can tell through slippages of their realities into the false realities – that they are living a fictional life, that they are performing. Eraserhead’s protagonist, like Laura, finds some solace in the stage. All characters, however, regardless of their comfort or discomfort on the literal or metaphorical stage – Laura Palmer, Henry Spencer, Fred Madison, Diane Selwyn, Nikki Grace, etc – are driven mad by their performances. They search for and cannot find, or cannot handle, or want to but cannot express, any kind of truth or reality.

For Lynch, all realities are performative, all performance is reality. What is real and what is performed roll into one. Social order is rejected and no one thing is truth: there are multiple truths, multiple realities, multiple potential reorganisations of the dismantled concept of contemporary social order.

The universe of Twin Peaks is a dismantling of our reality, the town of Twin Peaks is a dismantling of that universe’s reality, the Black Lodge is an absolute rejection of that universe’s reality, the ‘realities’ of all of which are fictional and the performances in all of which are symbolic rejections of social order. When a character performs in Lynch, dancing or singing or acting, they’re a carnivalesque reminder that there are no rules, there is no reality, characters are performing and know they’re performing and they’re no less real or fictional than the other performance.

Susan Blue is no more a performance than Nikki Grace. Betty Elms is no more fictional than Diane Selwyn. The Laura Palmer who performs her nights tied up in Leo’s cabin is no more real or false than the Laura Palmer who performs the role of the homecoming queen.

All performance in Lynch is acknowledgement of the performative nature of all things. All realities are unreal. All order is disordered.

Leave a comment