Not financial advice.

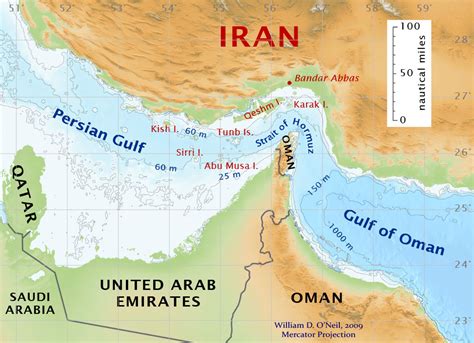

The Iranian parliament has endorsed the closure of the Strait of Hormuz, a vital choke point in global oil trade which sees the transit of around 20 million barrels per day (mbpd).

Closure of the strait, which still requires approval from Iran’s Supreme National Security Council to go ahead, would halt flows from Iraq, Kuwait, Qatar and Iran – all of which lack viable pipeline alternatives.

It appears geopolitical turmoil in the Middle East will catalyse the structural reordering of global oil trade logistics to favour other pipeline-rich exporters. This will inevitably cause long-term transformations in trade, investment and geopolitical alignment.

Assuming the Strait of Hormuz will be closed – through military force, since Tehran has no legal claim to block the waterway – global oil markets will need to respond quickly and pivot towards a handful of different suppliers and routes.

The Gulf’s centrality as a transit hub will likely diminish, with growing reliance on alternative pipeline corridors and non-Gulf producers. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates would gain strategic leverage, not only for their spare capacity but for their ability to physically move barrels without relying on Hormuz. Their pipelines may effectively become geopolitical lifelines for Western economies strapped for energy reserves.

Riyadh’s East-West pipeline can move about 5 mbpd to the Red Sea, while Abu Dhabi’s pipeline to Fujairah on the Gulf of Oman handles around 1.8 mbpd. These routes, in combination with Egypt’s Suez-Mediterranean pipeline and the Suez Canal, could reroute around 6 mbpd. Still, a substantial supply shortfall of more than 10 mbpd will remain, and Suez rerouting poses its own risks: Houthi attacks in the Red Sea and vulnerability to congestion or sabotage. Insurance premiums will therefore surge as geopolitical risk compounds transport costs.

Oil importers must seek to accelerate diversification strategies. As things currently stand, Japanese shipping company Nippon Yusen KK has instructed its vessels to keep safe distance from Iran while navigating the passage, and Qatar has instructed its tankers to wait outside the strait until ready to load.

Tougher decisions must be made in the critical days ahead, however, as the war enters a precarious and more volatile phase. India’s union minister for petroleum and gas, Hardeep Puri, has already signalled interest in West African grades and expanding storage. China, meanwhile, could look to reinforce ties with Russia or expand its use of overland routes via Central Asia. Over a more substantial period of time, new routes like the Northern Sea Route – seasonally viable but nonetheless nascent – may attract investment as the climate crisis reshapes Arctic accessibility.

West African and US suppliers will, in the main, become beneficiaries. Buyers such as India and China should increasingly turn to those regions for oil supplies. Shipping routes will certainly lengthen, raising costs and delivery times.

This may trigger least a short-term spike in oil prices – possibly beyond Monday morning’s (23 June) climb to more than $78 per barrel in early trading, marking 10 days since Israel’s initial strikes on more than 100 targets across Iran. The afternoon, however, saw a tumble in oil prices, as traders interpreted Iranian missile strikes against a US air base in Qatar as a sign might avoid attacking energy infrastructure.

Strategic reserves and spare OPEC+ capacity – estimated to be several mbpd – will go some way to stabilising the market within the first few weeks following closure. Regardless, in the medium term, rapid infrastructural investments and diversification away from the Gulf trade routes will need to accelerate if Western economies are to reestablish energy security.

The conversations unfolding now between governments, traders and investors will shape the next chapter of global trade.

Leave a comment